The true cost of the Alcohols, Ethanol & Methanol in pollution efforts

What happens to the amount of ethanol consumed by Americans when the federal government simultaneously mandates that an ever-increasing percentage of ethanol be added to gasoline while also subsidizing its production?

It skyrockets and affects other markets that rely on it like corn and feed production and any distillate based or reliant industry.

The Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 require that gasoline used in the United States has additives that oxygenate the fuel. The most common oxygenate was MTBE, which is being phased out due to harmful effects on human health. Both the House and Senate energy bill proposals in 2003 contain a mandate making ethanol the only legal oxygenate for meeting the federal fuel oxygenate requirement. But both versions of the energy bill also abolish the federal oxygenate requirement, but add a requirement to use ethanol as a renewable energy source. Navigating these political waters has been challenging for both politicians and the interests on all sides of the oxygenate debate.

The Environmental Protection Agency formed a Blue Ribbon Panel in 1999 to study the health benefits of fuel oxygenates. The Blue Ribbon Panel report highlighted the fact that the air quality benefits of oxygenated fuel are unclear. The environmental problems caused by MTBE reinforce that concern, but little analysis has addressed the combined air, water and soil effects of ethanol.

The Blue Ribbon Panel recommendation was to eliminate the oxygenate requirement altogether. In this study we perform a benefit-cost analysis of the ethanol mandate as an oxygenate; our findings support the recommendations of the Blue Ribbon Panel. We also analyze the political economy dimensions underlying the success of federal ethanol mandate provisions in both the House and Senate proposals. That success rests on the uncoupling of ethanol as a renewable energy source from ethanol as an oxygenate, a subtle piece of political rhetoric. We conclude that ethanol is not actually a renewable energy source, given the fossil fuel use required to produce ethanol.

We find that whether or not ethanol use generates net positive energy or net negative energy, ethanol-oxygenated reformulated gasoline uses more resources overall and does not pass an economic or environmental benefit-cost analysis. The fossil fuel energy used in producing and transporting ethanol imposes environmental costs, and whether or not ethanol produces negative net energy, its consumption also leads to costs. These costs outweigh the health benefits of ethanol use. Adding the cost of environmental detriment from agricultural runoff from growing crops for ethanol reinforces this conclusion.

Examining the political dynamics of the success of the ethanol provisions reveals that separating the fuel oxygenate issue from the renewable fuels issue has enabled Congress to satisfy both the strong farm and oil interests in the debate, even when ethanol does not make economic or environmental sense.

Thus although Congress is following the recommendations of the EPA’s Blue Ribbon Panel and eliminating the fuel oxygenate requirement, the bait-and-switch of ethanol from oxygenate to renewable fuel has created the opportunity for the ethanol industry to succeed politically, at a cost that is spread across all taxpayers, drivers, and natural resources.

Over the objections of oil refiners and automakers, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency endorsed the use of more ethanol-blended fuel in most passenger cars.

The EPA concluded it is safe to use fuels made with up to 15 percent ethanol in cars, SUVs and light-duty trucks manufactured between 2001 and 2006. That decision builds on an EPA decision from October 2010 to waive Clean Air Act restrictions on new fuels or additives and allow the ethanol-blended fuel, known as E15, for use in passenger cars built since 2007.

At the request of renewable fuels advocates, the agency had been deliberating whether the higher ethanol blend could be used in cars without damaging their emission-control systems.

The Energy Department and EPA have conducted studies of how the fuels would behave in newer cars.

EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson said recently completed testing and data analysis showed that E15 does not harm emissions control equipment in newer cars and light trucks.

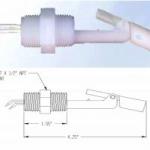

In older vehicles - it will likely soften and cause fuel line (hose type) and other failures over time.

The agency is holding off on granting a similar waiver to allow the use of E15 in motorcycles and heavy-duty vehicles, as well as non-road engines, since there isn't as much data about how the fuel would work in that equipment.

The decision is a victory for ethanol advocates, including manufacturers, corn farmers and their supporters on Capitol Hill.

Roger Johnson, the president of the National Farmers Union, said the decision would expand access for ethanol producers "and for farmers who produce clean, renewable energy solutions for our country."

The move paves the way for E15 to be used in roughly 60 percent of the domestic automobile fleet. It also helps fulfill a congressional mandate that at least 36 billion gallons of ethanol and other biofuels be mixed into transportation fuel in 2022, up from 9 billion gallons in 2008.

But Ethanol producers have pushed for the change as a way to boost demand for their product.

Rob Skjonsberg, the senior vice president of POET, the world's largest ethanol producer, said the EPA's decision "opens the door to solving the market barrier on ethanol use."

But oil refiners, of course which have fought the waiver in federal court, blasted the decision.

Charles Drevna, president of the National Petrochemical and Refiners Association, said the EPA was moving ahead "without adequate scientific evidence" that the higher ethanol blend doesn't damage equipment.

"Widespread use of 15 percent ethanol in gasoline could cause engine failures that could leave consumers stranded, injured or worse, and hit consumers with costly engine repairs," Drevna said. "It's the wrong decision at the wrong time, made for the wrong reasons."

Bob Greco, the director of downstream operations for the American Petroleum Institute, called the EPA's action "a rush to judgment" and noted a recent report by the auto and oil industries that documents possible performance problems with E15.

"EPA is choosing to ignore the potential red flags in its headlong rush to extend a premature waiver," Greco said. "Comprehensive vehicle testing of E15 by automakers and the oil industry is not yet complete. EPA is putting more American consumers at risk by approving the use of E15 without knowing the consequences it could have."

Early in January 2011, the refiners association asked a federal appeals court to overturn the waiver the EPA issued in October 2010. Auto industry trade groups also have challenged the EPA's ruling and warn that confusing labeling at filling stations could inspire motorists to pump E15 into motorcycles and older cars by accident.

The oil industry's fight against E15 has found an unexpected ally in environmentalists who say the production of corn for ethanol takes land away from food production, contributes to soil erosion and encourages the use of fertilizer that can contaminate water supplies.

The dividing line is in 1993, following the Energy Policy Act of 1992, which required specified car fleets to purchase alternative fuel vehicles capable of operating with E-85, an 85%/15% blend of ethanol and gasoline. In addition, the Clean Air Act amendments of 1990 required the wintertime use of ethanol in 39 major metropolitan areas and full-year use in nine others that had not satisfied the Environmental Protection Agency's imposed standards for carbon monoxide.

An attempt by Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-California) to drastically reduce subsidies for domestic ethanol production and cut the tariff on imported ethanol was ultimately unsuccessful, reports Reuters. The proposal would have cut the annual cost of subsidies by $5.3 billion.

Ethanol is the alcohol produced by the distillation of various kinds of vegetation and can be found in many products including antiseptics and beverages. Its use as an automobile fuel has boomed in recent decades.

The letter submitted by Sen. Feinstein was rejected by a bi-partisan initiative from mainly Midwestern senators, many of whom have received campaign contributions from companies associated with ethanol production and distribution such as Monsanto and Archer Daniels Midland. A contribution search at MAPLight.org, a nonpartisan research organization, reveals that pro-ethanol subsidy senators accepted substantially more funds from ethanol-related companies than did anti-ethanol subsidy senators.

The production and use of ethanol is a contentious issue. One one hand, the production of ethanol in the US reduces reliance on foreign oil imports and creates local jobs. It's also a renewable resource and releases fewer particulates when burned. However, growing the corn destined for ethanol production requires vast tracts of intensively farmed land whose nutrient content can eventually become depleted. The production and transportation of ethanol is also expensive; in many cases it's actually cheaper to import oil from abroad.

Feinstein said that ethanol has not fulfilled its promise to displace foreign oil, and that the tariff actually increases U.S. dependence on fossil fuel imports from the Middle East by discouraging imports of cheaper ethanol from more efficient producers in Brazil, Australia, and India.

And she is right. BUT . . . the only way to decrease emissions without complicated technology is to use a more "carbon-less" chain type of fuel in the first place - a cleaning burning fuel initially as Alcohol based fuels are.

Of the course the ONLY fuel that leaves NO POLLUTION at all is Hydrogen.

After that, it was off to the races for the ethanol-government industrial complex. Simply projecting a straight line from the trend between 1981 and 1993 would place 2010's ethanol consumption level below 5,000 thousand barrels per month. Instead, thanks to the federal government's subsidies and mandates benefiting ethanol producers, it has risen to be over 25,000 thousand barrels per month.

,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,